Francis Bacon’s Destruction of His Own Paintings: Understanding the Artist’s Turbulent Creative Process

Bacon’s destroyed works, often referred to as his ‘slashed canvases,’ offer significant insight into the way the artist viewed his own creations and himself, highlighting themes of self-sabotage, imperfection, and the ongoing struggle for meaning.

Why Bacon Destroyed Hundreds of His Own Works

Bacon’s destruction of his work was not indiscriminate. There was a method to the madness. Typically, he would target key figurative elements, often cutting out the heads or key components of the image, thereby nullifying the work's impact. These partial destructions seem deliberate, as Bacon could have fully annihilated the canvases by burning or otherwise completely obliterating them. Instead, his act of violence toward the paintings was often partial, suggesting an ambivalence—an emotional push and pull between creation and destruction, finality and the possibility of reuse. The fact that he left the stretchers intact, perhaps for reuse, further illustrates this conflict between wanting to erase a failed creation and still maintaining some connection to the material for future work.

These partially destroyed canvases, such as the forty found in his studio after his death and now housed in Dublin City Gallery The Hugh Lane, raise questions about Bacon’s intentions. Margarita Cappock’s 2005 publication of these ‘Destroyed Canvases’ has sparked further debate around Bacon’s mindset when committing these acts of destruction. Why did he stop short of total annihilation? One theory posits that Bacon’s slashing of these paintings, particularly focusing on the head, which in his work often serves as the seat of identity and emotion, reflects a deeper psychological self-destruction. Bacon, who struggled with his own identity and the existential meaning of life, may have seen these failures as symbolic of broader existential failures. By taking a knife to his creations, he could be seen as acting out a kind of self-sabotage, mirroring the internal turmoil that haunted him throughout his life.

While Bacon’s destroyed canvases were not initially intended for public display, they have since become objects of intrigue and speculation. Works that Bacon himself deemed ‘failed’ have found their way into public collections and private markets, even as fragments. This further complicates Bacon’s legacy, raising the question of whether an artist’s intention to destroy a work should be respected, or if the remaining pieces, however incomplete, hold artistic or commercial value. The violence Bacon inflicted upon his own work speaks to his profound dissatisfaction with his creations and perhaps with life itself.

Paintings are personal

Bacon’s destruction of paintings also invites comparisons with the theme of self-destruction in his personal life. Known for his chaotic and often self-destructive lifestyle, including heavy drinking, gambling, and tumultuous relationships, Bacon’s personal and professional lives were entwined with a sense of chaos and ruin. His destruction of paintings can be seen as a reflection of this. Rather than a clean and controlled method of disposal, his violent treatment of his canvases mirrors the turbulent forces that shaped his life and work. The act of destruction, often committed with a knife—an instrument of violence—brings to mind the mutilation and distortion of the human body that Bacon so often depicted in his paintings. The body, like the canvas, becomes a site of destruction, a battlefield where Bacon’s existential battles were fought.

Psychological

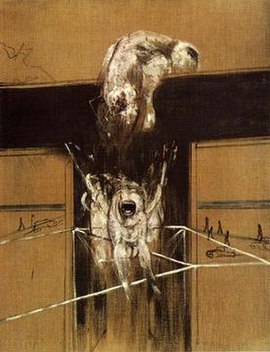

The psychological implications of this violence cannot be overstated. Bacon’s focus on the head in his paintings, a symbol of identity, emotion, and consciousness, is telling. In many of the destroyed canvases, it is the head that is slashed out or excised, rendering the figure faceless or incomplete. This act of removing the head seems to suggest a rejection of identity, a refusal to fully complete or realise the human figure. Perhaps for Bacon, the head, as the seat of consciousness and self-awareness, was too much to bear. By cutting out the head, he could symbolically destroy the self, leaving behind only fragments of what was once a complete figure.

'Finish'

Beyond his destroyed paintings, Bacon also abandoned many works, labelling them as incomplete or unsatisfactory. As noted by David Sylvester in a 1996 letter regarding Bacon's "Lying Figure" (c. 1953), works that were considered 'abandoned' during Bacon's lifetime were often still of immense artistic value. Yet, the idea of "finish" for Bacon was not the same as it might be for other artists. An atheist and a nihilist, Bacon’s only real concept of 'finish' was death itself. His reluctance to complete works, as evidenced by the many 'Studies' or the unfinished canvases like *Fragment of a Crucifixion* (1950), demonstrates his view of art—and life—as open-ended, incomplete, and forever subject to the chaos of existence.

Existential philosophy

In destroying his own paintings, Bacon was confronting this ambiguity head-on. Destroying a painting could be seen as an attempt to avoid the permanence of 'finishing'—to stave off the inevitability of completion, which for Bacon was akin to death. In this way, the destruction of his canvases becomes an extension of his existential philosophy. Even when his works did not meet his own exacting standards, there was a palpable reluctance to let them fully disappear, mirroring his own internal struggles with finality and meaning.

Discover our selection of Francis Bacon prints for sale and contact sales@andipa.com or call +44 (0)20 7589 2371 for further information.