Joan Miró., The Farm

Joan Miró’s paintings, with their swirling forms, vivid colours and dreamlike simplicity, remain some of the most distinctive and imaginative creations in modern art. But behind their playful appearance lies a deep and deliberate philosophy. For Miró, art was not simply about technique or tradition; it was about freedom — the freedom to see the world anew.

Central to this vision was his lifelong fascination with the folk art and children’s drawings of his native Catalonia. To understand why Miró was so inspired by these humble sources, we must look at both his personal history and his profound desire to reinvent the language of painting itself.

The Influence of Catalonia’s Folk Traditions

Joan Miró The Hunter (Catalan Landscape) 1923-4, Oil on Canvas. © 2025 Successió Miró / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Born in 1893 in Barcelona, Miró grew up surrounded by the vivid cultural traditions of Catalonia. The region’s folk festivals, rural customs, and artisanal crafts had a richness and sincerity that deeply marked his imagination.

Catalan folk art — colourful, fantastical, rooted in the rhythms of nature and peasant life — was an art of the people, unschooled yet brimming with symbolism, humour, and raw creativity. It was spontaneous, intuitive, and emotionally direct — qualities that Miró would seek to infuse into his own paintings throughout his life.

During his early years, when modern art movements like Cubism and Futurism were preoccupied with formal innovation and cerebral analysis, Miró looked backwards — towards something more organic and innocent. Catalan folk imagery, along with children's untutored drawings, represented to him a kind of primal visual language, uncorrupted by the intellectualism that he felt had overtaken European art.

Children’s Drawings: A Purity of Vision

Just as Catalan folk traditions captivated Miró, so too did the naive, instinctive creations of children. In their drawings, Miró saw an art form untouched by conventions of realism or academic discipline. Children, he believed, approached art with a sense of wonder, spontaneity, and imaginative boldness that adults too often lose.

Miró admired how children depicted the world not as it appeared, but as it felt — using exaggerated forms, strange perspectives, and whimsical details to capture the emotions and energy of their subjects. This emotional authenticity resonated with his own ambition: to strip art down to its purest impulses, reconnecting with a childlike, dream-driven vision of reality.

Rather than view children’s work as crude or primitive, Miró honoured it as deeply authentic — a guiding example of what modern art could aspire to be when freed from expectation.

The Catalan Landscape and Miró’s Dreamworld

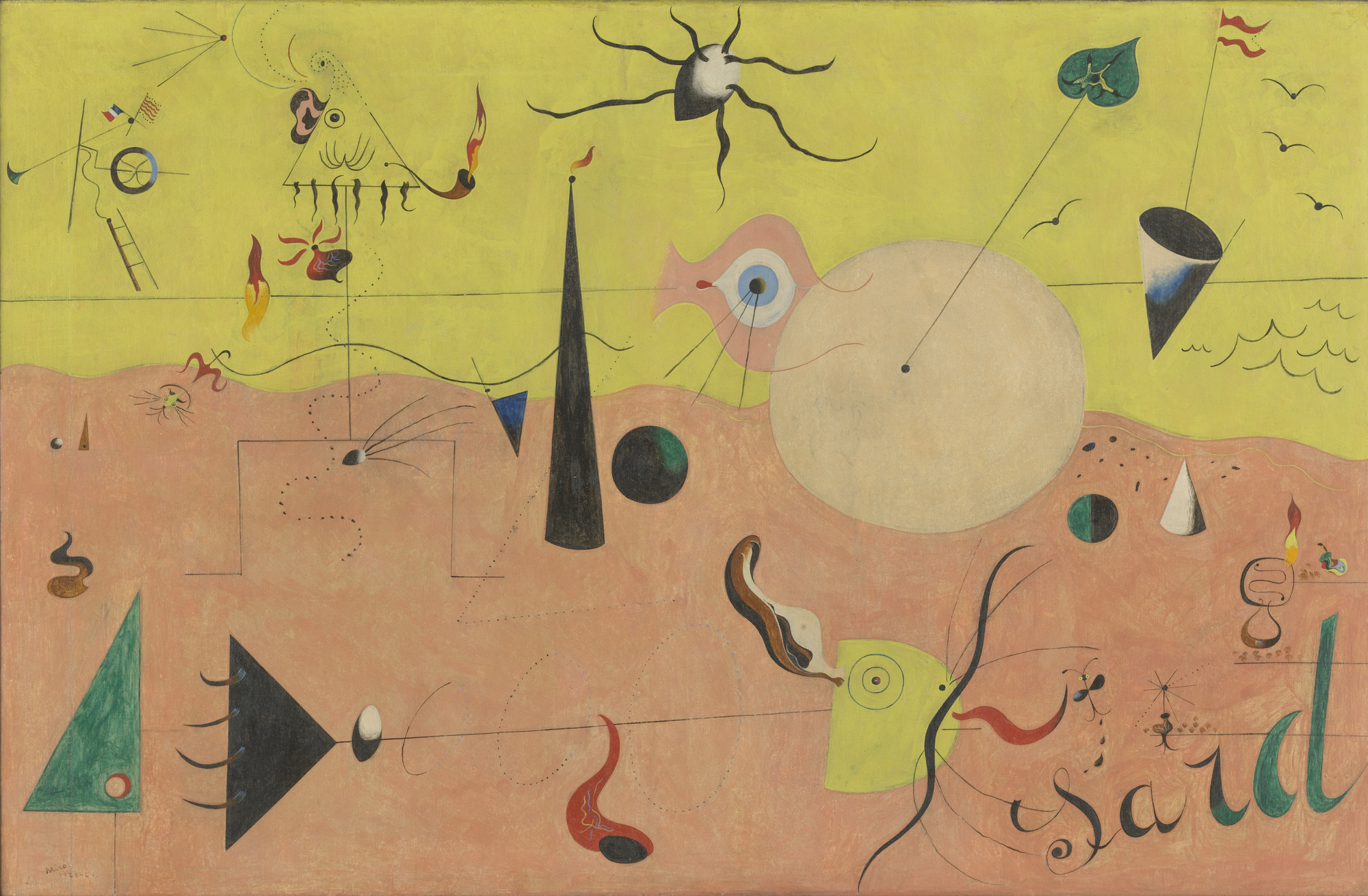

Joan Miro. The Harlequin's Carnival, 1924-5, Oil on Canvas. © 2025 Successió Miró / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

The physical landscape of Catalonia — its rugged fields, twisted olive trees, and boundless sky — also played a profound role in shaping Miró’s artistic vocabulary. In many ways, his paintings read like folk myths retold in paint, populated by stylised birds, sun-like faces, and surreal constellations.

In works like The Farm (1921–22), Miró captures rural Catalonia with meticulous detail, yet gradually dissolves realism into a symbolic, almost enchanted space. Later, in paintings like The Harlequin’s Carnival (1924–25), he abandoned detailed observation altogether, creating floating, biomorphic shapes and fantastical creatures — a visual language that owes as much to children’s imagination and folk symbolism as it does to Surrealist experimentation.

Catalonia was not simply a setting for Miró; it was a mythic homeland, a wellspring of creativity whose sights, sounds, and traditions animated the dreamscapes he painted for the rest of his life.

A Defiant Simplicity: Art Against Oppression

Miró’s embrace of folk and childlike imagery also carried political significance, particularly during the fraught years of Spanish civil unrest and later under Franco’s dictatorship.

By rooting his art in the popular, the primitive, and the collective, Miró rejected the authoritarian values of control, order, and hierarchy. His “naivety” was in fact a profound statement of resistance — an assertion that freedom, creativity, and imagination could survive even under oppression.

In later interviews, Miró spoke often of wanting to achieve an art that was "as simple as a child's", but one capable of carrying enormous emotional and symbolic power. For him, the elegance of a simple line or a floating shape could be an act of rebellion, an affirmation of life, joy, and boundless possibility.

Final Thoughts: Miró’s Enduring Simplicity

So, why was Miró inspired by children's folk drawings in Catalonia? Because in them, he found a model of authenticity, a vision of art as something instinctive, emotional, and unspoiled by convention. In the playful symbols and vibrant colours of Catalan folk culture, and in the raw creativity of a child's first drawings, Miró recognised the truest expressions of the human spirit.

This inspiration shaped a body of work that remains joyful yet profound, simple yet mysterious — and forever free.