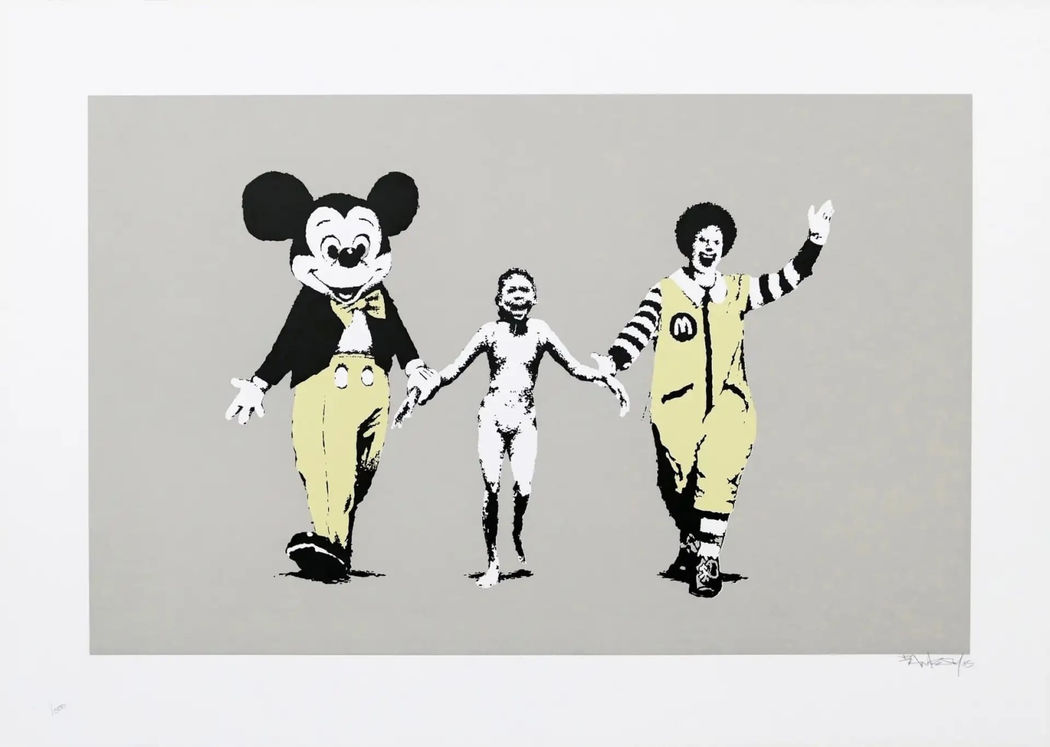

Banksy, Napalm Girl

The Terror of War (Napalm Girl): New Attribution Debate and Its Impact on Banksy’s Napalm

One of the most haunting and recognizable images of the 20th century is once again at the centre of global scrutiny. The Terror of War—better known as Napalm Girl—the Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph long attributed to Associated Press photographer Nick Ut, is undergoing a major re-evaluation. In May 2025, The Art Newspaper reported that World Press Photo has suspended attribution of the image after new evidence suggested that Ut may not have been the original photographer. Instead, credit may belong to one of two Vietnamese photographers present at the scene: freelance photojournalist Nguyễn Thành Nghệ or military cameraman Huỳnh Công Phúc.

This unprecedented move has triggered wide-ranging discussions surrounding journalistic ethics, accuracy in historical record-keeping, and the complexities of photographic authorship. Within the art world, however, the implications extend even further—particularly for Banksy’s 2004 screenprint Napalm, one of the artist’s most politically charged and disturbing early works. Banksy repurposes the Napalm Girl image with brutal clarity, using it to expose both the horrors of war and the ways global culture packages, sanitises, and commodifies human suffering.

A Symbol of War, Trauma, and Global Awareness

Taken during a South Vietnamese airstrike in 1972, the photograph captures nine-year-old Kim Phúc running naked down a road, her skin burned by napalm. The image circulated around the world, shifting public opinion about the Vietnam War and becoming one of the most influential photographs in modern history.

For decades, Nick Ut has been credited as the photographer, receiving both the Pulitzer Prize and World Press Photo of the Year. But the new documentary The Stringer casts doubt on this narrative. Eyewitness testimony suggests Ut may not have possessed the lens required to capture the iconic frame, raising the possibility that a Vietnamese photographer produced the now-famous image and that the work was later submitted under Ut’s name.

A Historic Decision: Suspended Attribution

Rather than transferring credit to a new photographer, World Press Photo’s decision to suspend attribution entirelymarks a historic first. The organisation emphasised that this is “not a retraction but a recognition of doubt,” acknowledging the complexity of reconstructing photojournalistic authorship amid the chaos of war.

This uncertainty prompts fresh questions about the legacy of the photograph—questions that resonate even more deeply when considering artworks that appropriate the image, such as Banksy’s Napalm.

Banksy’s Napalm: A Confrontation with Violence, Consumerism, and Cultural Memory

Among Banksy’s most provocative works, Napalm (also known as Can’t Beat That Feeling) directly recontextualises the Napalm Girl image. Banksy places Kim Phúc unchanged at the centre of the composition, flanked by smiling corporate icons Ronald McDonald and Mickey Mouse, who cheerfully hold her hands as though escorting her through an amusement park.

This grotesque, deliberate contrast weaponises the language of advertising to expose Western consumer culture’s relationship with violence, propaganda, and moral detachment. Whereas the original photograph depicts the raw horror of war, Banksy’s version asks viewers to confront how such images are circulated, commodified, and ultimately consumed by the same global systems that shape public opinion.

Authorship, Exploitation, and Historical Narrative

Banksy’s message does not depend on the photograph’s authorship. The power of Napalm Girl lies in its cultural ubiquity—reproduced in books, exhibitions, newspapers, and collective memory. Yet the new questions surrounding the image’s origin make Banksy’s critique even sharper.

If the photograph was inaccurately attributed and a Vietnamese photographer was denied global recognition, then the image’s history already contains an element of exploitation. This aligns directly with the themes Banksy exposes: the imbalance between those who shape narratives and those who live through the events depicted.

A Key Work for Collectors

For collectors, the renewed debate highlights the continued relevance of Banksy’s Napalm. Released in 2004 in an edition of 150 signed and 500 unsigned, it remains one of the artist’s most politically potent works. Unlike many of Banksy’s playful or satirical prints, Napalm is intentionally stark and confrontational—reflecting the gravity of its source image and the broader systems it critiques.

As the world continues to reconsider the origins of the Napalm Girl photograph, Banksy’s Napalm underscores a deeper truth: the most urgent question is not who pressed the shutter, but how images of suffering are used, manipulated, or monetised long after the moment they were taken. Few contemporary artworks address this with the same clarity and force.