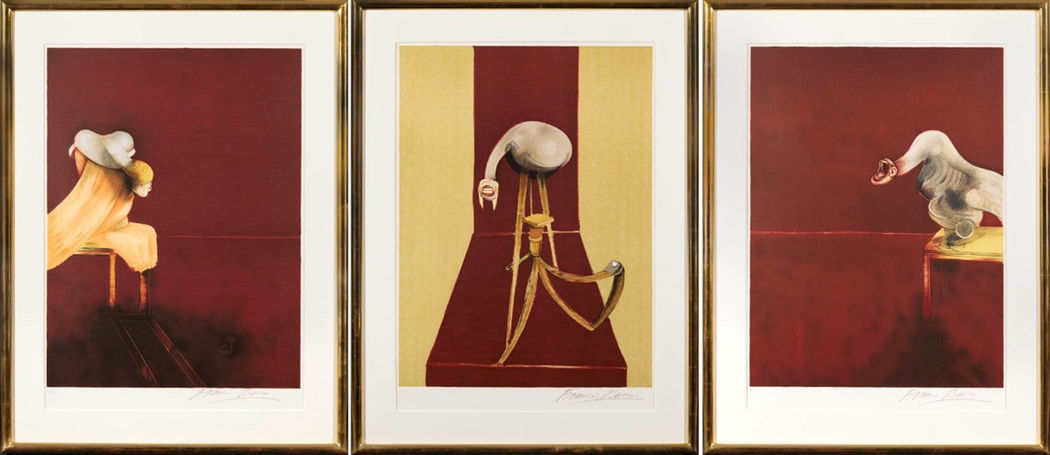

Francis Bacon After Second Version of the Triptych 1944, 1988, 1987

Triptych Format

Francis Bacon’s triptychs are among the most distinctive and powerful works in 20th-century art. They are instantly recognisable, not just for their scale and intensity, but for the way they distil his raw, unsettling vision into a three-part structure that is as formal as it is visceral. Bacon did not invent the triptych format; it has deep roots in European art, particularly in religious painting. But he reimagined it in a way that spoke entirely to the modern condition, stripping it of its original devotional purpose and transforming it into a stage for human drama, psychological tension, and existential truth.

Historical Roots

The triptych’s origins lie in the altarpieces of the Renaissance and earlier, where three connected panels were used to tell a religious story or to create a symbolic arrangement, often with a central scene flanked by supporting narratives. Bacon, who had an acute awareness of art history, understood this tradition well. He had spent hours at the Prado Museum in Madrid studying the works of Velázquez and the great Spanish masters, and he knew how the triptych could hold multiple moments or perspectives in a single work. But for Bacon, the triptych was not about guiding the viewer through a sacred story. It was about confronting them with different facets of a single, unresolvable subject. Bacon began working with the triptych format in earnest during the 1940s and 50s, but it became central to his practice in the 1960s and beyond. The structure offered him both discipline and freedom: discipline in the sense that it imposed a formal rhythm, three equal verticals, each a self-contained painting, and freedom because within that frame, he could fracture time, shift perspective, and explore variations on a theme without being constrained by the need to resolve them into a single image. In his hands, the triptych became a visual and psychological arena, a place where figures could be isolated, mirrored, or distorted, each panel intensifying the others.

Discipline, Freedom, and Psychological Depth

One of the key reasons Bacon gravitated towards triptychs was his resistance to narrative painting. He often spoke of wanting to capture “the brutality of fact” rather than tell a story, and the triptych allowed him to present multiple views of a subject without locking them into a single linear interpretation. In a work like Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion (1944), the panels don’t depict different moments in time or steps in a sequence. Instead, they confront the viewer simultaneously, their twisted, shrieking forms amplifying each other’s impact. The viewer is not led through a beginning, middle, and end; they are forced to hold all three images in their mind at once, caught in the tension between them. This simultaneity was crucial to Bacon’s vision. He believed that painting should operate more like memory or sensation than like cinema. Life does not unfold for us in a tidy narrative- we recall fragments, moments, and impressions all at once, often overlapping or contradicting each other. The triptych format gave Bacon a structure that mirrored this fractured, layered way of experiencing reality. It also allowed him to work through variations on a theme, painting the same figure or subject in slightly different ways across the panels. This repetition was not about redundancy; it was about deepening the viewer’s engagement, making them see and feel the subject from multiple angles.

Bacon’s triptychs also served a compositional purpose. By isolating figures in separate panels, he could intensify their psychological presence. Many of his works feature solitary figures in stark, almost stage-like settings, surrounded by empty space. The separation of panels turns each figure into an island, heightening the sense of loneliness and disconnection. Yet, because they are linked within the same frame, these isolated figures inevitably relate to each other: mirroring, echoing, or opposing each other in ways that generate a charged, unsettling energy.

Rejecting Narrative

Another reason Bacon returned to triptychs was the way they allowed him to engage with the idea of time, not as a sequence, but as a kind of suspended state. In some works, the three panels might depict a subject in slightly different positions, suggesting movement or transformation, but always in a way that resists a clear narrative. This ambiguity is part of what makes his triptychs so compelling: they feel both immediate and timeless, as if the events they depict are happening outside of linear time altogether.

Emotional and biographical contex

It is impossible to discuss Bacon’s triptychs without acknowledging their emotional and biographical context. Many of them were responses to loss, violence, or personal turmoil. The Black Triptychs of the early 1970s, for example, were painted after the death of his partner George Dyer. In these works, the panels become almost like the stages of grief, not sequentially, but simultaneously. They are spaces for meditation and confrontation, holding pain and memory in a suspended, permanent state. The triptych here becomes a form not just for representation, but for endurance. From an art historical perspective, Bacon’s use of triptychs can also be seen as a way of positioning himself within - and against - the great traditions of painting. The three-part format inevitably calls to mind religious altarpieces, but Bacon’s subjects are resolutely secular, often disturbingly so. In place of saints and angels, we have contorted bodies, solitary figures, and scenes of violence or intimacy stripped of sentimentality. This deliberate echo of the sacred format, now filled with the rawness of human flesh and experience, creates a tension that is central to Bacon’s work: the clash between the grandeur of tradition and the brutality of the modern human condition.

For Andipa Gallery’s collectors and viewers today, Bacon’s triptychs remain as arresting as ever. They demand a different kind of engagement than a single-panel painting. The eye moves back and forth across the panels, making connections, noting differences, feeling the pull of repetition and the resistance of separation. They are works that cannot be taken in at a glance: they require time, and they repay it with a depth of psychological and emotional complexity that few artists have matched.

Summer in Full Colour runs at Andipa until 30 August 2025. If you would like to buy or sell a print by Francis Bacon please contact sales@andipa.com or +44 20 7581 1244