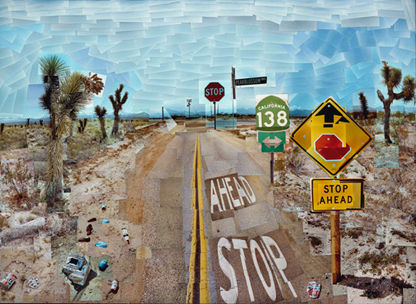

Pearblossom Hwy. 1986 No.1. Photographic collage on paper.

David Hockney’s photography is one of the most fascinating, inventive, and underappreciated chapters in the career of one of Britain’s most celebrated living artists. Known worldwide for his vivid, sun-drenched paintings of California swimming pools, Yorkshire landscapes, and intimate portraits, Hockney has also made extraordinary contributions to the development of modern photography. His photographic works, particularly the now-iconic “joiners,” are a powerful testament to his constant curiosity and refusal to be confined by tradition. For collectors, admirers, and those exploring Hockney’s practice through galleries such as Andipa Editions, his photography opens up an entirely different dimension of his artistic vision, one that challenges how we see, remember, and reconstruct the world around us.

In the early 1980s, David Hockney began experimenting with photography not as a supplement to his painting, but as a serious, standalone practice. Frustrated by the limitations of the single photographic image and inspired by the cubism of Picasso and Braque, Hockney developed his own visual language using a Polaroid camera and later a 35mm film camera. These photographic collages, constructed from dozens or even hundreds of individual prints arranged to form a larger image, were dubbed “joiners.” Unlike traditional photographs, which capture a single frozen moment, Hockney’s joiners unfold over time and space. They ask us to consider how we actually experience life: not in a single frame, but in fragments, glances, and shifting perspectives. His early works in this style, such as Pearblossom Hwy or Don & Christopher, feel both intimate and expansive, capturing not only scenes but the experience of looking at them.

Capturing Time and Space

What makes Hockney’s photography so compelling is the same thing that makes his painting so enduring, his relentless desire to push against the flatness of the picture plane. Whether using paint or Polaroids, Hockney wants to get closer to the truth of perception, which for him has never been static. His photographic collages are as much about time as they are about space. A portrait might contain multiple expressions of the same subject; a room might be captured from various angles at once. In doing so, Hockney plays with the idea that our memories and our visual understanding are never quite linear. This is not photography as documentary, but as interpretation; fluid, complex, and deeply personal.

At Andipa Editions, where Hockney’s limited edition prints and rare works are part of an ongoing conversation with collectors and the wider art world, his photography offers a bridge between disciplines. Those familiar with Hockney's lithographs, iPad drawings, or etchings will recognise in his photo collages the same playful intelligence, the same urge to deconstruct and reinvent. Just as his swimming pool paintings redefined light and colour in figurative art, his joiners redefined what a photograph could be, not simply a record, but a constructed vision. For collectors, this opens up a fascinating avenue. Hockney’s photographic works are not as widely known or circulated as his paintings or prints, but they are just as significant in understanding the full arc of his creativity.

From Analogue to Digital

What’s also striking is how Hockney’s photography ties into his larger, ongoing investigation into technology and image-making. Long before smartphones made panoramic photography ubiquitous, Hockney was physically cutting and arranging prints by hand to achieve a similar effect - but with a distinctly human touch. His approach is tactile and analogue, yet conceptually advanced. In later years, as he moved on to using iPhones, iPads, and multi-camera video installations, the seeds of this digital experimentation can clearly be traced back to his photographic collages of the 1980s. In this way, his joiners aren’t just a curiosity or a detour, they’re a crucial step in his lifelong attempt to make pictures that reflect how we actually see the world, rather than how a camera tells us we should see it.

Hockney’s photographic practice also reflects his deep connection with his subjects, often friends, lovers, and the spaces they inhabit. The portraits feel especially intimate because they reveal time unfolding within them. A face might appear twice in the same image, or an arm might subtly shift from one frame to another. These anomalies aren’t errors; they’re part of the point. Hockney invites us to see people and places not as static objects but as living, breathing presences. In this sense, his photography is far more painterly than many would expect - full of warmth, movement, and complexity. For collectors drawn to emotional richness in visual art, this body of work holds deep appeal.

Today, as David Hockney continues to work with new media well into his 80s, the relevance of his photographic explorations remains strong. In a visual culture dominated by fast, disposable images, his joiners ask us to slow down, to consider, and to look again. They remind us that seeing is not passive; it’s a creative act. For those who collect or admire Hockney’s work through Andipa Editions, there’s immense value in revisiting these photographs not only as artworks but as philosophical propositions. They question the authority of the single viewpoint and celebrate the messiness of lived experience.