Alex Yellop: Alex, thanks for sitting down with us and taking the time to visit. I think we've kind of touched on it in our emails, but essentially to start, let’s look at the idea of the maps being something quite playful and quite fun I suppose.

Alex Kent: I think so. And there is, yes, a sense of playfulness, and as you say, a sense of fun. But I think this is juxtaposed with a sense of anxiety. Both of the pieces we are talking about today really oscillate between playfulness and anxiety; the playful approaches that Grayson brings and this inherent sense of anxiety that speaks to us through his experience, maybe his childhood experience, especially.

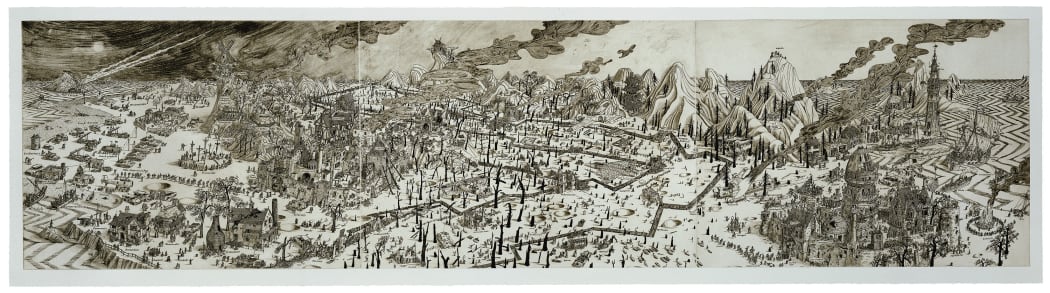

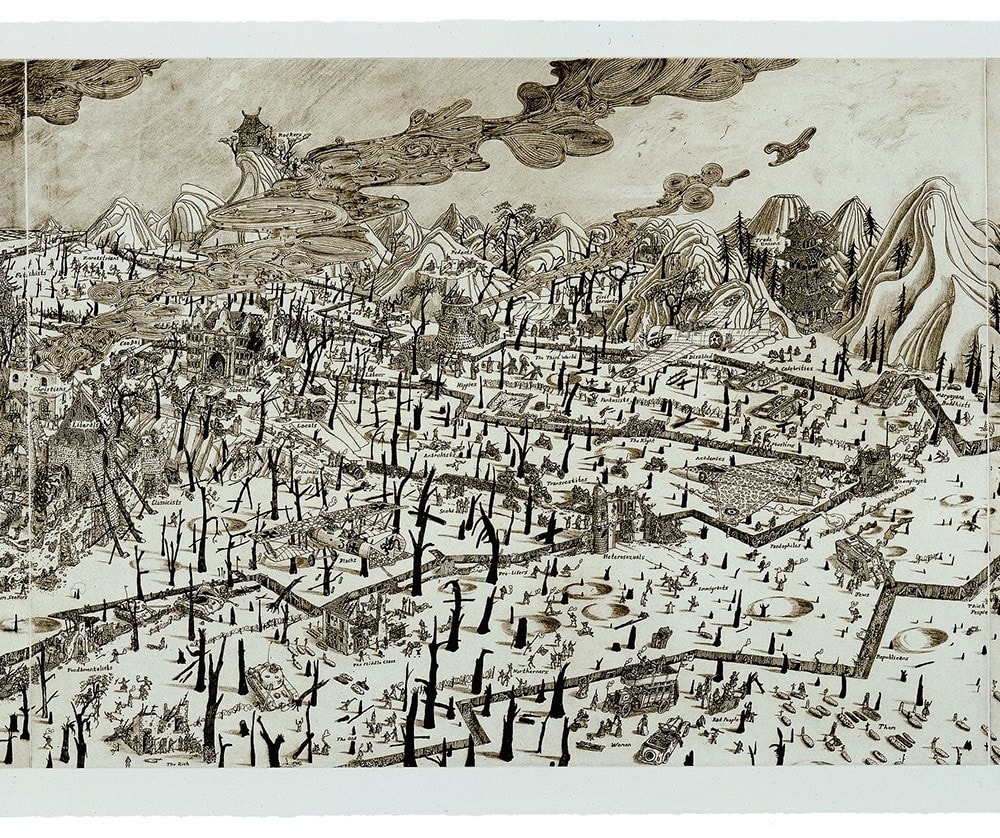

But what strikes me is how he tells his point of view from a cartographic aspect. It is very interesting how he has turned to mapping as a sort of personal journey, like the pre-scientific mappings we used to see. The Map of Nowhere draws on the idea of a mediaeval Mappa Mundi, rather like it was inspired by the cartoon- like caricature stereotypes, especially with the Hereford Mappa Mundi, you've got these cyclops for example, and people with big feet and all sorts of things. In a way, there is this sense of a fantastical, and I think Grayson does exactly the same sort of thing, but it's a very introspective view, instead. And this idea, then, comes from a cartographic perspective that's almost ascientific and much more about the personal.

And so I think Map of Nowhere reveals something quite interesting about what maps do, in terms of how we look at the world and as a form of language for externalising how we process and experience the world that's come to the fore recently as an art medium in itself. There is something about maps that oscillates and hinges between certainty and uncertainty, and between representation and non- representation. I think that the whole idea that Grayson brings, as you said, is sort of playfulness in a way that goes against what a lot of maps do and what they are to a lot of people, which is to present the sense of certainty and like...

Alex Y: ...like an element of fact, I suppose, today, isn't it?

Alex K: Exactly. I think Grayson has said maps satisfy this craving for certainty that we have and it's almost as if the map has emerged as this particular type of graphic, you know, for the human journey...

Alex Y: Absolutely.

Alex K: A playful approach that he brings to that whole idea is something really worth understanding, because it resonates to us now in a sort of ascientific, in a sort of post- scientific way, because it's a medium that is so versatile. It can be very much about exactitude and science and measurement and so on, but also it can be about embodying personal experience and trying to convey that. And a cartographer would say that cartography is about communication; it's about communicating something of a place. In many ways, obviously, art is about communication, but the joining of the two that you see with Grayson's insights that he brings, I think there's something really quite special about that.

Alex Y: I suppose, what you said about presenting fact; there's an objectivity to a map, and he kind of spins it in the sense that there's a subjectivity because he's exploring himself. There's that autobiographical element, and it's that marriage that you said, brings these two kinds of, no pun intended, I suppose, worlds together.

Alex k: I think you're absolutely right. You can't talk between certainty and uncertainty without faith playing a big role. You look at a map, for example, where it is?, Is it something internal or external? It shows something external. And you have faith in the map that it's going to show you something truthful. About what it is that you are and what you’re wanting to look at.

And I think it is really interesting when that is turned around to be a very introspective way of looking at the world. Or looking at what you are within, for example, and then the narratives that the map enables you to weave because of that. And the way that maps spatially. As well, it allows a very different way of thinking.

Looking at Print for a Politician, I think that's really interesting how, again, there is this idea that is playful and so on, and this, this idea that we're sort of stereotypically looking at enemies and to almost kind of see all of these as equal, these different factions that he's put there. It’s also a very relativistic piece, but at the same time it makes you think, where would I fit within that myself? So it is kind of funny how he turns the spectacle back on you. I think that's very interesting. An interesting thing for a map to do, to sort of make it reflect back on you and to make you challenge what your beliefs are. Usually we look to a map to tell us something: you should believe this, you should believe that. And in fact, that's maybe something that he does through this piece as well, that it turns the idea on its head that when you look at a map, you're wanting certainty, a certain view of the world. He turns that round to say, well, You know, it's not certain. Where is your certainty? So again, it sort of comes back to that idea of maybe of doubt. There's that sort of uncertainty, that anxiety that is at the heart of a lot of this I think. It's interesting because he covers so many different factions. It's a very interesting perspective that you have about it, turning it back on ourselves in a way.

Alex Y: He covers issues that I think are uncomfortable. And he touches on a million different issues. I suppose political, economical, societal you know, all of these big, almost abstract concepts that exist within society, the world, and what we've created as a species. And it's interesting that he brings it to the forefront of our attention. There's a kind of sense of uncanniness to these maps. These caricatures that are, are quite innocent, they're not photorealistic images or highly detailed kind of drawings. There's this sense of almost like a childlike innocence addressing these really powerful concepts that exist within our society. And it's again, this tension that oscillates, as you said at the beginning, between these two different worlds that he's creating and asking us to kind of jump into. I guess that in a funny kind of way, using the medium of the map to do that is a very profound statement that he makes because it utilises the power that maps have and their authority that maps embody. And rather interestingly, again, sort of jokes with that a little bit in an almost like childlike, kind of uncanny, almost naive perspective.

Alex K: The way that they're drawn is not what you'd expect from, let's say modern cartography. The other key thing about modern cartography, you don't see people and, since the enlightenment really at least, you know, people have been filtered out.

So it’s sort of anti-objective almost, not that it's not subjective, but there's an anti-objectivism going on here that the objective can't exist. So it presents something that challenges what you are expecting from a map. And funny enough, again, as a cartographer, one of the key things you are thinking about is the user of the map. When you are designing the map, you are thinking about what and who the users are and the potential that you're wanting to fulfil. Now that's obviously very much to do with design because you're thinking about function and so on. Like think of the Tube map and Harry Beck's idea that has become obviously very well used and famous. People saw something in that and obviously replicated it, but I think rather interestingly there is something again that perhaps Grayson does to sort of turn that idea in its head, Because again, it's sort of asking the question, what do you want from this map? From this piece of art, you know, what is it that you bring to this?

And again, with cartography, I think again, there is this whole idea that actually what you bring to the map is really quite crucial. The map doesn't do it by itself, but it is through the interaction that you have with it. That actually it is created and made and that it has infinite possibilities and that's what makes it quite exciting looking at them. Especially with these works, when one looks at them they have their own connotations, their own memories that are inspired and stimulated by it.

Alex Y: That’s a fascinating insight. To look at it like that, and I suppose in the sense that that's potentially a bit where the function meets the concept of art and then subjectivity comes back into it. So it (Grayson’s map) kind of moves and inhabits all these different spaces at once in that sense, because, you know, using the example of the Tube map’s achievement and it being both an exceptional design and incredibly practical. Whereas this is a kind of map that allows you to imagine.

Alex K: The works allow you to properly navigate Grayson's experiences, maybe his memories, his fears, his dreams, his hopes, where he's interacted, or where things have intersected throughout his life. But then I really like the idea that you mentioned a bit touching back on you as the viewer. And I think it is this great dialogue that can be established between somebody looking at something and bringing their own subjectivity to it.

Alex Y: A map is only useful if it's in front of something, if it isn't being viewed, if it isn't being used, it kind of loses that power that it has. And then I guess over time new discoveries are made and new measurements. Cartographers are able to enhance and add more detail as the technology evolves.. It's interesting, maybe the concept of a map becoming redundant, and I wonder where his maps could fit into that. If he evolves as a person or as an artist, will there be a time where this map was just a part of his life and then it's kind of moved on from.

Alex K: And he's expressed what he's thinking, his memories, his feelings, through the map. And interestingly again you bring this idea of navigation and so on, but also there is the meditative aspect of really looking at the map and how it is immersive and captivating. And that in itself is actually really interesting because we don't see so much of it these days, of course. In mediaeval times, you would have maps used as substitutes for pilgrimage and this sort of thing. So, it wouldn't necessarily be that you would use a map for navigation, but you would, for example, think about the journeys that you might go on. It was a way in which information could be communicated to people that weren't literate.

Again, the Mappa Mundi at Harford Cathedral, people would see it and they would learn something about the world based on largely biblical knowledge at the time with Jerusalem at the centre. It is a sort of interesting use of how that is turned around so that it is about the internal meditation and pilgrimage through your life. And if there were to be a map like this for everyone, of course they would be very different. They'll have our own highs and lows. That also speaks to another element of cartography, which is really about generalisation and the crucial function, or process I should really say that a cartographer goes through, which is, selection: what is supposed to be on the map and what isn't. You can't show everything. So it's all about selection and what goes into that selection is hugely important. And we can look at, for example, ordnance survey maps where you used to have big blank areas that were these sort of silences that would hide the location of something that would need to be kept secret.

Alex Y: And again there is the idea of bringing truth to something and the element of hiding something away for the benefit of someone or something such as an idea or a concept.

Alex K: Yeah. I think that's really interesting because if you are thinking about a sort of mapping phenomena in a way it's a similar but a different process to, if you were to turn that around introspectively. What are the bits of my experience that I want to capture, that I want to transform into something on the map and what does that mean? Because when you go through that process, as a cartographer, again, you are choosing things that you think will be for the benefit of the user. That's why you choose whatever you need to show on the map. And if you look at the tube map, again, obviously it's tube lines, but you know, the topography is abandoned in favour of the topology, the connections and so on, because that's what was deemed to be important.

And it's important for the users. But if you turn that around, so it's actually a map of yourself, and your experience, you still have to go through that process of thinking what is it that's going to be included. But the question would be, who is it for? Is it for yourself you are doing this for? Is it for your later self? and that might be an interesting thing to ask Grayson though.

So the things that you've chosen, were they the right choices for you as a later artist looking back?. Would you say they were the right things that you chose to show? The other big question is how you are going to show something.

It's more about, again, the expression. So again, it is interesting this sort of continuum between communication and expression and usually cartographers would say that they're focused on communication, but quite often it's really about expression as well. The other thing that you touched on, which I really like, is this idea of a sort of redundancy and maps being redundant because of falling out of use, and one of the genres of maps that I've been studying for the last few years is Soviet maps. And that's very interesting and how they have been rediscovered in the 1990s.

Millions of these maps were made and huge amounts of work went into them, huge efforts that went in through satellite mapping, all sorts of things to create these maps that ultimately didn't fulfil the purpose to which they were intended during Cold War. And yet they've resurfaced and now are a huge source of interest. Not just in the sense that this is interesting, not just in terms of their historical value for looking at say the industrial heritage and that sort of thing but also for their aesthetic value.

And there is something again about the choice in what to show and how to show it that shines through as well as the aesthetic drive which I think is inherent to cartography Often people talk about mapping and power going together. But there's also a tremendous if not greater drive which is an aesthetic one. I think with cartographers, they want to create something that they are pleased with and they want other people to see that.

Alex Y: I guess it goes back to the idea of an artwork being produced. Are you doing it? Is this being done for yourself or do you need an audience for this? For it to fulfil its potential that is. And with Perry, it’s the execution of his works as well. Etching itself is an old technique that allows these beautiful details to have that mediaeval feel to them. And I think it works on so many levels. It’s a really clever piece and I've always enjoyed it (Map of Nowhere). It's so nice to get your perspective on it and kind of revisit it. And also, I guess in a sense, when you revisit, you're going back to a place and a map itself can guide you there. And I think his works function in a very meta kind of way. It's almost like an in-joke.

Alex K: And kind of a satirical look at the modern age again, there is something of the anxiety of the age that is captured. But also there is the satire, I think on what we are looking towards maps to provide, you know? Yeah. There's very much a kind of an introspective look on cartography that he's been able to tap into and express, which is quite difficult to see elsewhere. Because maps, again, have this inherent authority and seriousness. So it's like the message of what he's trying to convey is actually quite a serious one. But he's using the sort of creative pastiche of what mapmaking is all about, which is rather interesting.

So it's not just this sort of flat dimensionless, robotic procedure of recording everything. Yeah. Whether it's a very human process. Yeah. I think, and that's, something that he's aligned to very well, particularly in the sort of post-enlightenment kind of idea of cartography, where again, we try to make everything very objective as possible. And again he turns that around. shines light on the fact that cartography really isn't, it cannot be purely objective. And sometimes you need artists to articulate that in ways that academics and photographers can’t.

Alex Y: It’s interesting to think of the map as a piece of power and in this postmodern world it's taking that back from the state or these bigger ideas into the self. It’s this shift that we've seen across societies the last, well probably you could say forever, but I mean the last like 50, 60 odd years where we’ve become very much more individualistic and moving away from these big institutions. And it's the individual popping up and saying, well actually, you know, I'm gonna question the world in which I've been born through my own experiences. And it isn't relying on an institution to provide something to guide them per se.

Alex K: I suppose the obvious connection there is if you use something like Google Maps or whatever to navigate. Obviously you've got a homogenous view and everywhere looks the same pretty much, you know, through style, and that reason is a practical one. But of course the fact that now you have location based navigation, where through gps you'll know where you are located, your map will be updated. So it is ego-centric. In that way, in terms of location, but not ego-centric in the sense of your experience. And I think, you know, that again it is something which is just as you're saying is very, very interesting. I think that's maybe a step away from the sort of worldview that cartography has traditionally portrayed which is to say that this is the definitive way the world is. You think of ordnance survey mapping, and so it's a national landscape that they're mapping and if we've sort of grown up and got used to that, that's kind of how we see our own country and place within it.

A lot of research that I've done over the years has been looking at how different places map and record and you see these different countries have got their own way of looking at their own landscapes.

Alex Y: Is there a standardised method of ordnance surveying or does it vary between regions of the world?

Alex K: Absolutely. So different countries will have national mapping agencies and they will decide how to map their country, what they're going to show, what not to show and how to show it. So elements of style really come across very strongly. And again, I suppose, you know, I was writing about this almost 20 years ago. That was really a time when people were hanging onto this idea of objectivity in cartography. Especially rather with something very scientific like a topographic map that's based on observation and survey. How could there be any other view of landscapes? Then you just have to look across the channel and you can see how different French maps of their landscape are and how the French National Mapping organises their information. There are cultural reasons and societal reasons why certain things go on certain maps and that’s really fascinating.

Alex Y: I didn’t realise there was such diversity in mapping. I thought there was very much an international standard.

Alex K: That's exactly what the assumption would be. Certainly with something as practical as a map, but no, it's very much diverse. There are a set of standards, there was an EU directive that was several years ago about how data should be structured and organised and that sort of thing.

But in terms of portrayal and how you portray landscape that's very much down to national mapping organisations. And it's interesting that it’s objective. It's like they're really expressing the nation.

So, for example, Ordnance Survey recently have said that they will have a consultation on whether we want to have some new symbols which is quite an amazing step to announce as it’s often very closely guarded. Which in turn introduces the concept of these agencies being slightly mythical and plays on the idea of the myths that surround landscapes.

Alex K: One thing that immediately stands out to me is just how layered this work (print for Politician) is because, funny enough, when you make maps these days you are thinking in terms of layers a lot of the time. So different layers are different themes of information. Let's say for example you're making perhaps a tourist map of the town or something like that. You would have layers of information like buildings, symbols, maybe car parks, toilets, that sort of thing. And also some landmarks that are in the town. You might have rivers, of course roads and these would be stored in layers and created in layers that you would bring all together. And I think there is a change in how a mediaeval map or pre-enlightenment map would be more holistic to how more recent maps tend to be more objective.

Alex Y: I wonder if that ties in potentially with the idea, you touched it at the start of our conversation around the Mappa Mundi, you know, having very much a biblical sense. There is that element, again, of legend, this holistic approach to seeing and presenting the world that has changed as we have become increasingly scientific and individualistic. You know, our ability to research and to gather what we would call more objective information has improved over the course of the centuries.

We hope you have enjoyed part one of our conversation. For more information on our Grayson Perry prints for sale and to buy an original Grayson Perry ceramic, contact Andipa via sales@andipa.com or call +44 (0)20 7589 2371