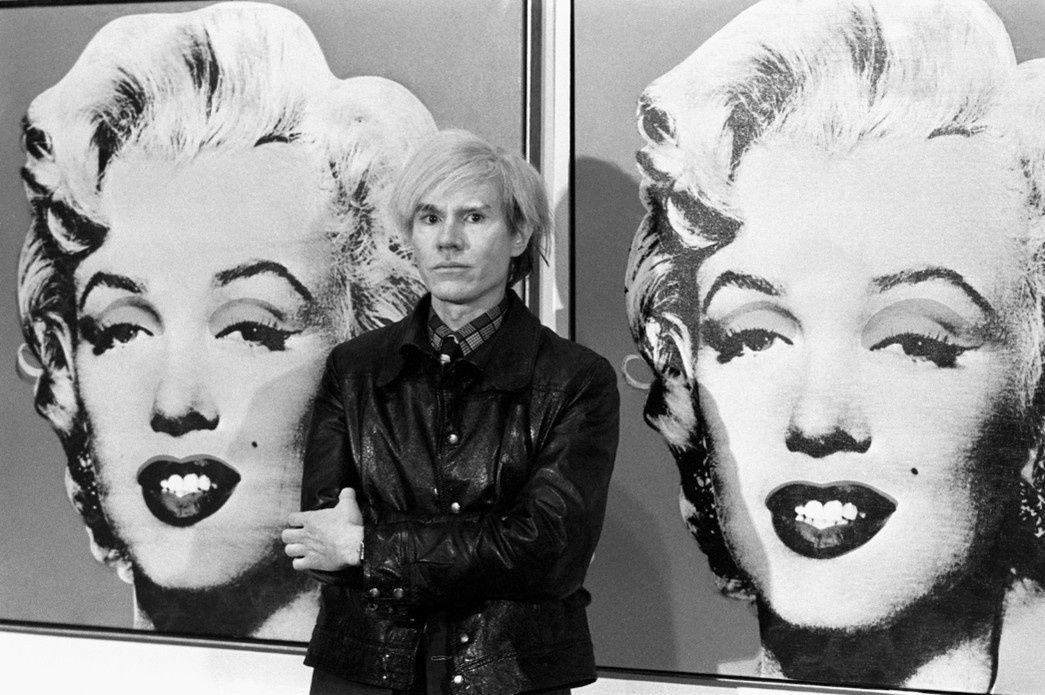

Andy Warhol at Tate Millbank, UK, in 1987. Image credit: PA Images via Getty Images

Andy Warhol remains one of the most recognisable figures in modern art, his name virtually synonymous with Pop Art. More than thirty-five years after his death, his work continues to speak directly to the world we live in today, arguably even more so than it did in his own lifetime. To understand why, it’s worth looking at who inspired him, how those influences shaped his vision, and why the themes he explored still resonate so powerfully in our commercial, image-saturated culture.

Early Life and Influences: Pittsburgh to Pop Art

Born in Pittsburgh in 1928 to working-class immigrant parents, Warhol grew up in a home where the visual world of religion, popular magazines, and advertising intersected. The golden saints and luminous faces of Byzantine icons in the family’s church existed alongside glossy Hollywood publicity shots and consumer advertising torn from the pages of Life and Vogue. From an early age, he was immersed in two very different but equally powerful visual languages: one sacred, steeped in symbolism and ritual; the other secular, fuelled by glamour, aspiration, and the promise of consumption. When Warhol later studied commercial art at the Carnegie Institute of Technology, he absorbed the mechanics of selling through imagery; the clean lines, bold colours, and clear messages that defined mid-century advertising. This education didn’t just teach him how to create images; it gave him the framework to understand art and commerce as two sides of the same coin.

Marcel Duchamp, Johns, and Rauschenberg: Shaping Warhol’s Vision

Artistically, Warhol drew from several key figures. Marcel Duchamp was a pivotal influence, having redefined art in the early 20th century with his “readymades”- ordinary manufactured objects presented as art. Duchamp’s challenge to the boundaries between art and the everyday resonated deeply with Warhol, who would later swap urinals and bicycle wheels for Campbell’s Soup cans, Coca-Cola bottles, and Brillo boxes. For Warhol, these items were the icons of post-war America, as culturally charged as any traditional subject from art history. From Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, he took the idea that popular imagery could be incorporated into fine art, but he went further, removing the painterly touch that still lingered in their works. Warhol embraced silkscreen printing, a commercial technique that distanced the artist’s hand from the finished product, reflecting the mass-production methods through which the images themselves entered the public consciousness.

Celebrity Culture and the Rise of Iconic Imagery

Warhol’s fascination with celebrity culture was also shaped by the glamour photography of the Hollywood studio system and the mass media’s power to create icons. He saw how a publicity still of Marilyn Monroe or Elvis Presley could become as ubiquitous and recognisable as a brand logo, and he was fascinated by the process that transformed a person into an image. For Warhol, the celebrity was not just an individual but a constructed identity, a product to be packaged, sold, and consumed by the public. This understanding, rooted in both his early experiences and his sharp observation of the culture around him, would form one of the central pillars of his art. These influences crystallised into themes that remain remarkably relevant: consumerism, celebrity, repetition, and the collapse of the barrier between high and low culture. In the 1960s, the idea that a painting of a soup can or a screenprint of a tabloid headline could stand alongside a Renaissance portrait was provocative, even shocking. Today, those choices feel almost prophetic. We live in a world where brands wield as much cultural influence as political leaders, where celebrities are commodities in their own right, and where images are reproduced, remixed, and shared in an endless loop. Warhol’s art anticipated the way images would dominate not only advertising and entertainment, but personal identity itself.

Between Art and Commerce

One of his most radical positions was the idea that there was no true divide between art and commerce. His Brillo Boxes looked indistinguishable from the supermarket packaging they mimicked, making the viewer question what separated one from the other. This collapse of categories feels even more relevant in an era of influencer marketing, brand collaborations, and curated online personas, where commercial identity and personal expression are deeply intertwined. Warhol also understood the power of repetition, using it to strip an image of its original context and turn it into something new. Rows of identical Marilyn Monroes or electric chairs mirrored the relentless visual bombardment of advertising while also creating a strange detachment; the more you saw the image, the less connected you felt to its original meaning. In today’s algorithm-driven feeds, where the same images and formats appear over and over, this rhythm of repetition is part of our daily visual experience. Warhol’s celebrity portraits, particularly those of Marilyn Monroe, also reveal his sensitivity to the way fame can dehumanise. His Marilyns are vibrant, seductive, and instantly recognisable, yet the repetition makes them ghostly. The image becomes an icon unmoored from the real person, her features flattened into a logo-like symbol. In our current cultural climate, where public figures are carefully managed media brands, Warhol’s work reads almost like a documentary on the mechanics of fame. His portraits are not celebrations of the individual so much as dissections of their image, showing how glamour and tragedy can exist in the same frame.

Repetition, Authenticity, and the Mechanisation of Art

Another enduring aspect of Warhol’s art is his challenge to the notion of authenticity. By using mechanical reproduction, he questioned the romantic ideal of the artist’s touch and the uniqueness of the art object. In the 1960s, this was a provocation; now, in the age of digital reproduction, filters, and AI-generated imagery, it’s a lived reality. Warhol’s work anticipated a culture where the originality of an image might matter less than its circulation, where its meaning comes from its ubiquity rather than its singularity. This is why Warhol remains so relevant. His themes are not relics of the 1960s, they are structural truths of modern life. The way we consume products, the way we construct and market identity, the way commerce shapes culture, these are all things we navigate daily, often without realising it. Warhol’s genius was to see these patterns clearly and to create art that both reflected and questioned them.

For collectors today, Warhol’s work offers more than bold colours and instantly recognisable faces. It’s a lens on the forces that shape our lives, a reminder that art and advertising, culture and commerce, are not enemies but partners in a dance that defines much of what we see and value. In bringing Warhol into the conversation at Andipa Editions, alongside other modern and contemporary masters, we are reminded that truly great art doesn’t just belong to its own time, it continues to ask questions, provoke thought, and illuminate the world long after the moment of its creation. Warhol’s influences shaped him, but his vision has shaped us, leaving a legacy that is as alive in the age of Instagram and global brands as it was in the New York of the 1960s.

Summer in Full Colour runs at Andipa until 30 August 2025. If you would like to buy or sell a print or original painting by Andy Warhol please contact sales@andipa.com or +44 20 7581 1244