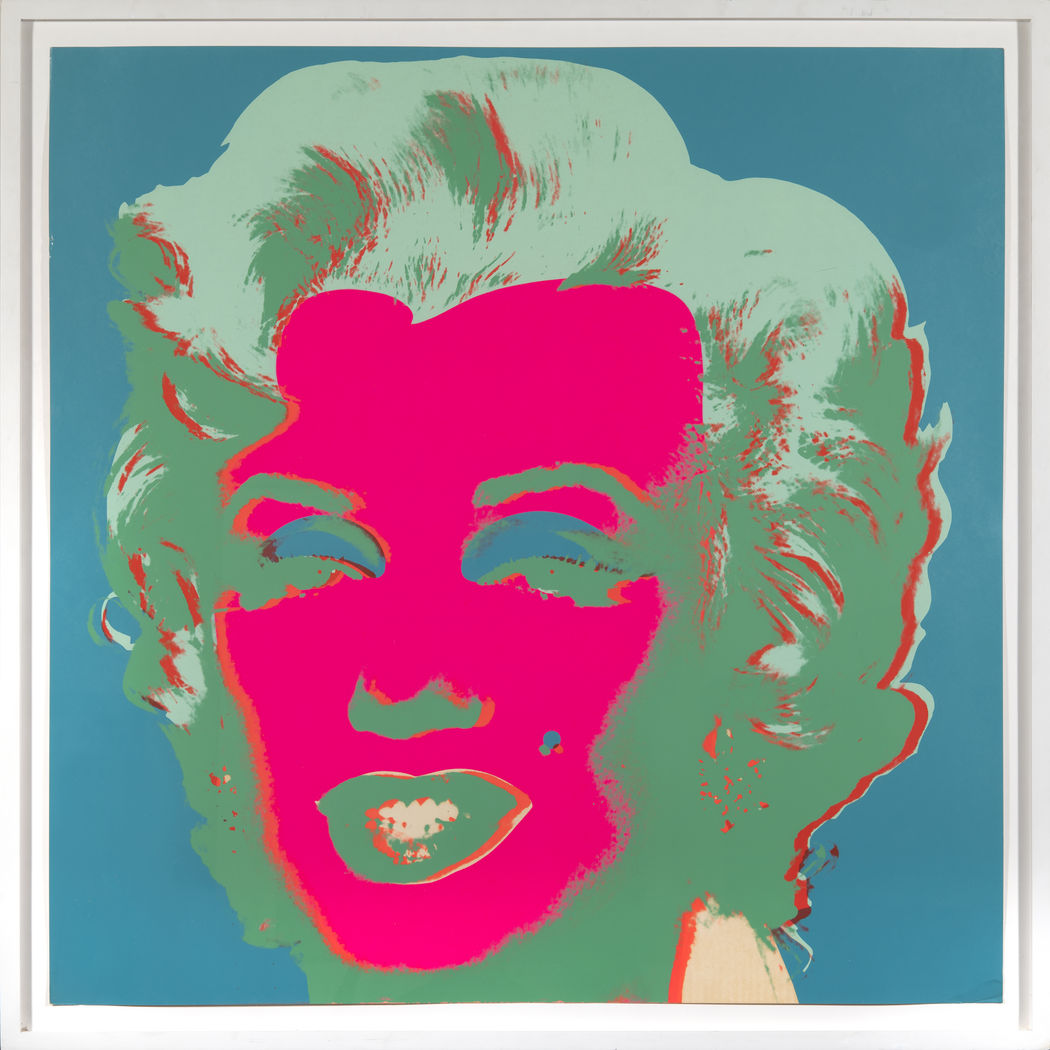

Andy Warhol, Marilyn Monroe (Marilyn) (F & S II.30), 1967

Andy Warhol and the Cult of Celebrity

Andy Warhol’s fascination with celebrity was not merely an aesthetic choice - it was a diagnosis of modern culture. Long before social media and the 24-hour news cycle, Warhol understood that fame itself had become an industry, and that the faces of stars were as much commodities as the products they endorsed. His screenprints of Marilyn Monroe, Mick Jagger, Judy Garland, Ingrid Bergman and James Dean are not portraits in the traditional sense; they are meditations on the fragile boundary between the human being and the manufactured image. For collectors, these works remain among the most coveted, not simply for their visual power but for what they reveal about Warhol’s acute understanding of fame, desire, and the myth-making machinery of modern life.

The Marilyn Monroe Phenomenon

Warhol’s approach to Marilyn Monroe remains perhaps the most recognisable expression of his celebrity iconography. Created in the wake of Monroe’s death in 1962, his Marilyn Diptych and subsequent screenprint variations transformed a single publicity still from the film Niagara into a repeated grid of colour and decay. In multiplying her image, Warhol both immortalised and obliterated her. The repetitions flatten emotion and personality, turning Monroe into an emblem of the tragic loop of fame: endlessly consumed, endlessly reproduced, ultimately hollowed out. For Warhol, Monroe was not just an actress—she was the perfect synthesis of beauty, vulnerability and mass production. Collectors are drawn to these works not only for their radiant Pop colours but for their haunting psychological undertone. Warhol’s Marilyn is both goddess and ghost, radiant and fading in the same breath.

Mick Jagger: The Living Spectacle

Where Monroe embodied the archetype of the consumed star, Mick Jagger represented the living, breathing spectacle of celebrity at its most vital. Warhol and Jagger were friends; their relationship was personal and collaborative. In 1975, Warhol produced a portfolio of ten screenprints depicting the Rolling Stones frontman, each image taken from Polaroids shot in Jagger’s home. These are among Warhol’s most dynamic works—gestural, sensual, charged with movement. The bold outlines, hand-drawn details and slashes of colour give the impression that Jagger is both subject and participant, co-author of his own myth. The prints capture the swagger and charisma of the rock icon, but they also expose the mechanics of performance: Jagger as actor, seducer, product. Unlike Monroe, Jagger’s fame is not passive; it is aggressively self-fashioned. For collectors, this series represents Warhol at his most electric—where friendship, art and commerce collide in perfect balance.

Judy Garland and the Elegy of Fame

In contrast, Judy Garland’s portrayal in Warhol’s Blackglama (Judy Garland) of 1985 is steeped in irony and nostalgia. The source image comes from the Blackglama mink advertising campaign whose tagline—“What Becomes a Legend Most?”—could have been written by Warhol himself. Garland, by then long deceased, was transformed once again into a glamorous yet ghostly emblem of fame’s price. The fur coat, the direct gaze, the flawless lighting all speak of luxury and allure, yet Warhol’s use of bold blocks of colour and visible silkscreen marks fracture the illusion. Garland’s life, marked by extraordinary talent and personal turmoil, becomes a parable in Warhol’s hands—how the culture that exalts its idols also devours them. Collectors often sense in these later celebrity works a tone of elegy; Warhol, approaching the end of his own life, seemed increasingly aware of fame’s corrosive edge.

Ingrid Bergman: Glamour and Distance

The Ingrid Bergman series from 1983 extends this meditation with a cool, detached glamour. Warhol’s three prints—With Hat, The Nun, and Herself—are based on film stills and promotional images of the Swedish actress. Here, Warhol blurs the line between role and identity, using Bergman’s face as both an object of beauty and a mask. In With Hat, inspired by her role as Ilsa in Casablanca, Bergman gazes off-frame, her features divided by shadow. Warhol’s title, notably, does not reference the character but the actress, reducing her to a visual type—a “with hat,” a cinematic trope. The result is an image at once intimate and impersonal. For collectors, these works highlight Warhol’s fascination with the intersection of cinema, advertising and personality. The coolness of the surface conceals a deep empathy for his subject—Bergman, like Monroe, was both adored and constrained by the image the world demanded of her.

James Dean: The Eternal Rebel

James Dean occupies a special place in Warhol’s pantheon of icons. Though the artist never met him, Dean’s early death and enduring myth as the eternal rebel epitomised the kind of fatal glamour that fascinated Warhol. His print James Dean, Rebel Without a Cause distils that legend into a single moment—youth, defiance, and mortality suspended in ink and colour. Warhol’s generation had grown up idolising Dean; to reproduce him decades later was to acknowledge both the persistence of his myth and the machinery that sustained it. Dean’s image is smooth yet brittle, as if made to crack under its own weight. For collectors, this work speaks to the romanticism of loss and the timeless allure of the doomed star—an obsession that threads through much of Warhol’s oeuvre.

What binds these portraits together is Warhol’s unflinching understanding that in the modern world, fame had replaced divinity. The saints and icons of earlier centuries had given way to film stills and magazine covers. Through his mechanical process—repetition, silkscreening, the use of commercial materials—Warhol elevated publicity into iconography. Yet he was never cynical. His affection for his subjects was genuine, even tender. He once said, “I love Los Angeles. I love Hollywood. They’re so beautiful. Everything’s plastic, but I love plastic.” That paradox defines his celebrity portraits: sincere adoration expressed through artificial means.

For Andipa collectors, Warhol’s celebrity works remain among the most powerful and investable statements of twentieth-century art. They are not just portraits of Monroe, Jagger, Garland, Bergman or Dean—they are portraits of us, of our collective obsession with fame and surface. In a world still driven by image and immediacy, Warhol’s vision feels more prophetic than ever. Each silkscreen is a mirror, reflecting both the brilliance and the emptiness of our desire to be seen. Collecting Warhol today is to hold a fragment of that mirror—to possess, for a moment, the shimmer of immortality that every star once promised.